Global Sociology and the deep time of infrastructure

Global sociology, by its definition, extends over multiple scales, tracing the operation of power between the global and the local. It challenges the social sciences to move beyond Eurocentric theories and develop methodologies and lexicon that captures the uneven geographies of knowledge that structure our understanding of the world. Building on this understanding, this post reflects on the recent rise of the infrastructural turn.

Over the past three decades, an interdisciplinary field of infrastructure studies has emerged across various disciplines, including science and technology studies (STS), sociology, and geography. Research in this regard has shown that infrastructure is bound up with political authority, social life, and urban spatial change. It highlights various tensions between instruments of governance—policy, regulation, and practices—and the imaginations and “poetics” that infrastructures evoke. Indeed, various scholars have called for examining the social, political, aesthetic, and ethical choices embedded in the design, construction, and maintenance of infrastructural systems, treating them not as neutral backdrops but as constitutive sites of urban life and transformations.

Early contributions to infrastructure studies—while recognizing that infrastructure is relational and differently experienced across social groups—tended to cast it as largely invisible; that is, “largely responsible for the sense of stability of life in the developed world” (Edwards, 2003) and as a hidden substrate that “becomes visible upon breakdown” (Star, 1999, p. 382).

This claim of invisibility was increasingly challenged in the following decade as scholars foregrounded Indigenous, racialized, and Global South experiences. Nelson (2016), for example, disputes breakdown-centrism by showing how resistance to colonial infrastructures interrupts their smooth operation and thereby renders them “apprehensible”. Research from the South has similarly demonstrated that roads and railways often function as racialized boundaries, restricting Indigenous people’s mobility and disciplining their time. Moreover, by dismantling communal infrastructures colonial governments often enforced relations of dependence and economic captivity. Nevertheless, it had frequently been framed as a national resource that ought to be protected from Indigenous populations, particularly as its disruption would adversely affect settlers’ modern life. Thus, in colonial and settler-colonial settings, infrastructures could not be pushed to the background and be considered invisible. However, instead, they were revealed—seen and made legible—through the frictions of governance, resistance, and everyday use

Figure 1: A water station stands in front of an “unrecognized” Bedouin village in the Naqab, while the village’s residents themselves have no access to water. Photo: Courtesy of Ameer Makhoul.

While the geographical scope has widened, many studies still operate within short temporal frames, often tied to specific regimes or development projects. Such discussions, I think, resonate with Santos’ question, “when was the global?” which builds on Stuart Hall’s (1996) invitation to think “at the limit,” and explores the meaning of the “post” in postcolonialism and what the answer entails. These insights redirect our attention to the histories of routes, architectures, and knowledge of infrastructure—particularly in networks that imperial powers have introduced to the Global South.

Recent research on the socio-political dimensions of infrastructure that challenge conventional temporal boundaries has adopted a longue durée approach. Such studies demonstrate that earlier—often colonial—projects have endured or provided the foundations for contemporary infrastructural systems, thereby continuing to shape the material and political conditions of infrastructural life today. Using the longue durée approach to infrastructure, Enns and Bersaglio (2020) demonstrate how contemporary mega-infrastructure projects in Kenya and along Tanzania’s Central Corridor have perpetuated colonial legacies, sustaining uneven patterns of (im)mobility that were established during the Scramble for Africa and reinforced in the post-independence era. Similarly, Terrefe and Verhoeven (2024) offer a longitudinal account of the Horn of Africa’s infrastructure, tracing the co-production of infrastructure and sovereignty over roughly 150 years. They argue that this entanglement has been a defining feature of regional politics.

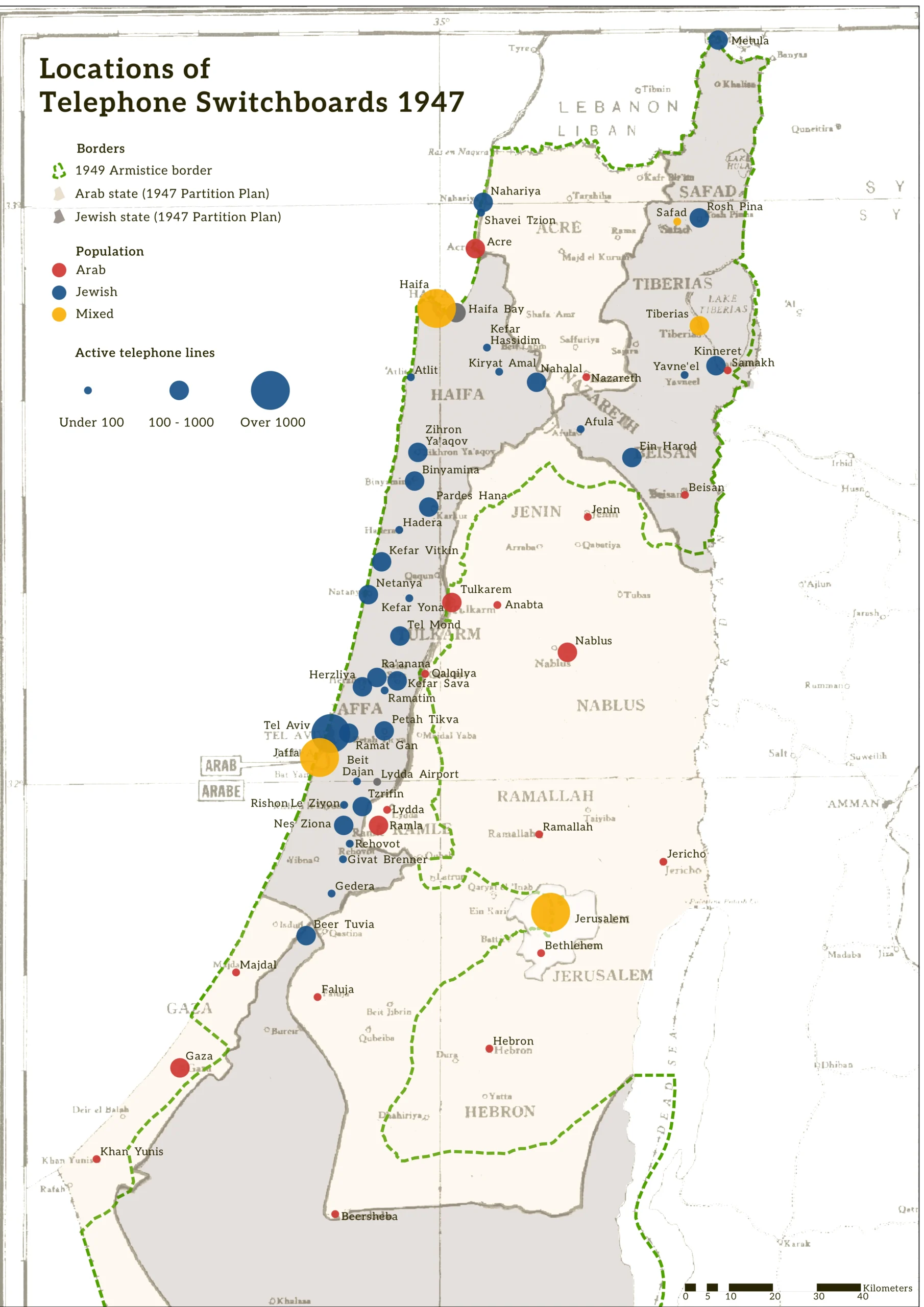

In a similar vein, a study I jointly conducted (Sa’di-Ibraheem & Wilkof, 2025) on telephone infrastructures in Palestine/Israel demonstrates that extended temporal analysis does more than disclose resemblances or continuities in power relations. It also reveals distinct mechanisms and practices which have had a cumulative impact of infrastructural inequalities over time. The telephone sector in Palestine, for instance, which the British developed unevenly during their Mandate, giving priority to the Jewish settler population, particularly in rural areas, was inherited after 1948 by Israel. Thus, Israel was left with a landscape in which Jewish settlements were well-connected through a developed telephony network, while Palestinian villages were left as virtual terra nullius in infrastructural terms. The new state (1948), viewing the Palestinians who remained within its borders as a temporary problem, initially pursued policies of displacement and population transfer, and the telephone became both an instrument and a rationale for exclusion and dispossession. During the Military Government era (1948-1966), while telephony services were selectively extended to Arab localities, they functioned less as means of connectivity and more as mechanisms of control, surveillance, and social engineering. Requests for connection to the telephone line were granted selectively, rendering the telephone network a key apparatus through which the state reproduced hierarchies, dependence, and exclusion.

Figure 2: Location of switchboards in Palestine by the end of 1947. Map taken from Sa’di-Ibraheem & Wilkof (2025), prepared by Bar Weinberg.

Tracing the (de)developments of the telephone infrastructure since its beginning unveils how events and changes in political and economic regimes, such as the end of the British Mandate, the establishment of Israel, the privatization of the telecommunication sector in the 1980s and the introduction of new technologies such as the Fiber optics, cannot constitute a proper “beginning” for the research. Furthermore, our findings illustrate how today’s uneven telephone provision in Israel reflects sedimented rationalities and decisions that have spanned the last century.

In sum, this text endeavours to bring global sociological reflexivity to infrastructure studies, illuminating both the epistemic and material architectures of inequality. In this regard, the longue durée approach, briefly presented here, enables a more comprehensive understanding of how infrastructures operate not merely as conduits of power but as terrains where alternative futures can be imagined, negotiated, and sometimes foreclosed. Moreover, it highlights how infrastructures are embedded in authority and difference across time, and how they are used to reproduce past hierarchies through modes of governance, as well as how their very persistence challenges conventional narratives of rupture and progress. However, this approach also raises pressing questions, such as how infrastructural studies can develop their epistemologies and avoid reproducing Northern temporalities and assumptions of linear development. What methodologies are best suited to capture the slow, cumulative operations of infrastructural power without losing sight of the everyday agency that reconfigures it? Moreover, ultimately, how could an attention to the longue durée open conceptual and political space for developing new ideas about infrastructures—not only as remnants of empires, but as potential grounds for reparation, repair, and more just futures?

Cite this article as: Sa’di-Ibraheem, Y. (2025, November 4). Global Sociology and the deep time of infrastructure. Global Qualitative Sociology Network. https://global-qualitative-sociology.net/2025/11/04/global-sociology-and-the-deep-time-of-infrastructure/

References

Edwards, P. N. (2002). Infrastructure and modernity: Force, time, and social organization in the history of sociotechnical systems. In T. J. Misa, P. Brey, & A. Feenberg (Eds.), Modernity and Technology (pp. 185–226). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/4729.003.0011

Enns, C., & Bersaglio, B. (2020). On the coloniality of “new” mega‐infrastructure projects in East Africa. Antipode, 52(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12582

Hall, S. (2002). When was ‘the post-colonial’? Thinking at the limit. In I. Chambers & L. Curti (Eds.), The Postcolonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons (pp. 242–260). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203138328

Nelson, C. A. (2017). Slavery, geography and empire in nineteenth-century marine landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315087917

Sa’di-Ibraheem, Y., & Wilkof, S. (2025). Cabling and un-cabling Palestine/Israel: Toward a theory of cumulative infrastructural injustice. Political Geography, 116, 103242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2024.103242

Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

Leave a comment